Table of Contents

March of 2011. After a couple of moderately successful decades, the Italian gaming industry was facing its worst crisis yet; only a couple studios survived the dawn of the 2010s, and the country was still reeling from 2008’s global recession. Because of limited funds and developers leaving the country to work abroad, games made in Italy seemed destined to fail. The industry needed a wake-up call, perhaps with the help of the state which, up until that point, had mostly ignored games (except to try and ban some of the more violent titles).

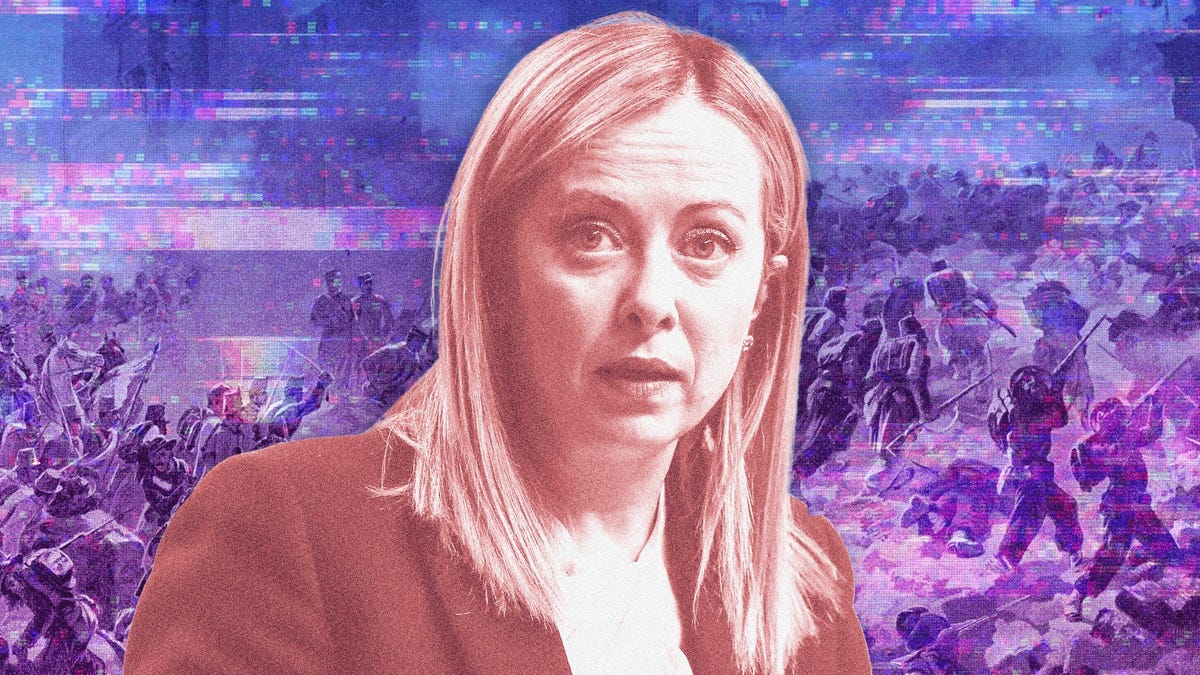

Enter former Minister for Youth Policies and current Italian prime minister Giorgia Meloni. In her younger years when she supported neo-fascist movements—which, she says, she has since distanced herself from—she was also quite the self-proclaimed nerd. Meloni was known as Khy-ri in the old IRC chat network #undernet, one of the first Italian online communities dedicated to “nerds” and fans of fantasy. In her role as Minister for Youth, Meloni insisted that gaming was an important industry for Italy. Despite her vocal positive reinforcements, however, not much had yet been done to actively support an industry in crisis.

Until a strange new game called Gioventù Ribelle.

Then-president Giorgio Napolitano first revealed the game during the sesquicentennial celebrations of November 2010. Gioventù Ribelle (Rebellious Youth), he said, aimed to celebrate Italy’s 150th anniversary, a tribute to the struggles of the country’s founders.

Made entirely in Italy, the game would let players experience the thrill of fighting during the days of the Risorgimento, the 19th century movement for Italian unification. Its first level would be based on a single historical event: the 1870 breach of Porta Pia, when the Italian army invaded Rome, ended the Vatican government, and completed the union of the country. Meloni referred to Gioventù Ribelle as something of a history lesson: “Learning who we were and [who] we are today gives us hope for future generations,” she said. “This is…the meaning behind Gioventù Ribelle.”

On March 15 2011, a few short months after its initial reveal, Gioventù Ribelle was presented by its supervisor, Raoul Carbone (at the time a professor at the European Institute of Design in Rome), at the Maxxi Museum in Rome in front of several producers of the Italian Association for Multimedia Works (AIOMI). Carbone lauded it as a game that could compete internationally with the most advanced first-person shooters on the market. During the announcement (embedded above), neither Carbone nor Meloni provided additional information as to who developed the game. It surprise-launched shortly after the presentation.

What followed was the Italian gaming industry’s biggest scandal, one that threatened to forever ruin its reputation. Gioventù Ribelle was an unmitigated disaster, a half-baked game running in a development build littered with historical inaccuracies. Its creators pulled it off the internet almost as quickly as it appeared, leaving others in the industry to try and suss out what the hell had just happened. For years, its questionable developmental process remained mysteriously obscured, obfuscated by Carbone and others.

I spoke to several people involved in the project (behind the scenes as well as developers and critics working in the industry at the time) to try and understand what happened to Gioventù Ribelle and its botched celebration of Italy’s 150th anniversary.

The launch

Gioventù Ribelle was meant to be a traditional first-person shooter. Players took on the role of an unnamed hero tasked with bringing a message to the Pope during the 1870’s fight to breach the walls of Porta Pia. The official website instructed you on how to run the game from the Unreal Development Kit (with lines like “press ALT+ENTER to display in full screen” and “select Map A”), as it was not released as a download on Steam, the leading PC platform, or via other traditional methods. Players of Gioventù Ribelle described it as an incomplete and frustrating experience with installation problems, subpar graphics, bugged mechanics, and leftover assets galore.

In the single playable level available (which could be completed in around five minutes), you traversed the grassy Roman countryside, infiltrated a nondescript tunnel (supposedly, ancient Roman catacombs), explored the Quirinal Hill, and emerged in the middle of a bloody battle with Papal guards in order to hand the Pope that precious letter. A “full” version was promised that would feature another two levels set during different phases (and presumably different locations) of the fight for the unification of Italy.

But mere hours after Gioventù Ribelle’s launch, online forums were flooded with complaints and confusion. “It crashes continuously!”, “Wait, can you shoot the pope?”, and “This is the worst thing I’ve ever played” were just some of the comments. Italian sites began to wonder what was going on with the game. It even got the attention of American website Destructoid, which wondered “is this Italian shooter as bad as Big Rigs?”.

The problems were vast and obvious: enemy AI spent most of their time frozen eerily in place, your character was invincible, and when the AI did finally break free of their invisible bonds, they’d hit every shot they took. The typical mechanics one would expect from a FPS simply did not work.

Gioventù Ribelle was also full of historical inaccuracies, like weapon sound effects befitting a more modern game and period-inaccurate papal attire. Video game critic Simone Tagliaferri told me via phone call that, “the game was supported by the Museum for the Italian Risorgimento, which was strange since Gioventù Ribelle seemed to have nothing to do with actual history.”

Along with the “shooting the Pope” bit, which can happen right as the singular level is ending (as the player is also bizarrely free to shoot any NPC), Gioventù Ribelle features the infamous Unreal Tournament announcer screaming “first blood” or “killing spree” as you play through it—which certainly wasn’t tonally accurate for a game set in 1870. It was, quite simply, a mess.

Gioventù Ribelle was pulled offline by its mysterious dev team just a few days after its debut, on March 24, 2011.

As Tagliaferri suggests, the dev team did not appear to be supervised by a historian—but it also wasn’t clear who actually did work on it. Names were kept off the credits, save for Carbone and a few other “supervisors.” In the aftermath, as more and more people began asking questions about the promises made and promises missed with Gioventù Ribelle, a clearer picture began to emerge. And it wasn’t a pretty one.

The mysteries of development

The original website for Gioventù Ribelle draws a bold comparison: “A group of young men and women helped in unifying Italy during the Italian Risorgimento; in the same way, a group of ‘young rebels’ is now trying to send a strong signal: Italy has exciting and important stories to tell…”

But Gioventù Ribelle did not tell an exciting and important story, and didn’t help the sorry state of the local industry, Italian game developer Federico Fasce recalled via Facebook messenger. “We used to hang in a forum called Playfields, a few of us independent Italian developers, wondering what to do to survive in a struggling industry.” At the time, the only big name on the scene was Milestone, the studio responsible for the Screamer and MotoGP series. Ubisoft Italia, which would later go on to success with the Mario & Rabbids series, had just started out and was still incredibly small. But Gioventù Ribelle was clearly not what was promised—it didn’t reinvigorate the local industry. In fact, it almost destroyed it.

“It was very sad for us to see how the people behind Gioventù Ribelle were actively avoiding saying the truth about the game’s nature,” Fasce tells me. The project was originally described by Carbone as “being able to compete internationally with some of the best games out there,” but as development details began to leak online, its subpar presentation made more sense.

User Schaty, in a March 18, 2011 post on the gaming forum Multiplayer, alleged that Gioventù Ribelle was developed by him and seven other students as their final thesis project at IED, the same university where Carbone was himself a professor. “Everything was decided months ago, but they only told us in February,” he wrote. “We only had a few weeks to work on this project, not even time to sleep. While working on the game, we still had to study and prepare for our exams…” The comments on his post were a mix of incredulity and frustration: “Are you telling us that the sesquicentennial game was entrusted to a group of students with no budget?” wrote one user. “Moreover, where, on the official website, can we read the info you gave us?”

Schaty could not be reached for comment, as the user profile on the forum no longer exists, but Carbone would later confirm some details in a March 22, 2011 open letter: “The project, having been done by students for free, with no technical/economical support from other companies or people, would be unfairly described as lackluster, since it cannot be compared to similar commercial products or fan games done by people with much higher technical skills.” As far as anyone could tell, Carbone’s letter was the first time anyone involved with Gioventù Ribelle had admitted that student developers were responsible for the game.

The letter stated that the project was done for free, and the objective was “making possible investors aware that video games represent an economic opportunity, often ignored in our country.” But the original Gioventù Ribelle site listed sponsors, including national railway company Trenitalia and television service Rai.

Fasce and Tagliaferri both confirmed to me that public funds for the development of Gioventù Ribelle, during its initial development period, were often quoted to be around half a million Euros. “It was supposed to be money spent for marketing, if I remember correctly,” says Fasce. So where did the money go?

Carbone concluded his open letter with a bold statement: The project was entirely successful in its objective. “Confindustria [the Italian employers’ federation and national chamber of commerce] is receiving a lot of significant interest from large- and medium-sized Italian companies, which seem to be ready to evaluate the possibility of investing in the production of games made in Italy,” he wrote.

But that didn’t seem to be the case, as no substantial gaming companies were founded in the country in the months after Gioventù Ribelle’s launch, nor were any significant new titles announced to be in development.

The creation of the Italian IGDA

Fasce recalls that the announcement of Gioventù Ribelle was, at least, the spark for the creation of the Italian chapter of the International Game Developers Association (IGDA) in January of 2011. And its failure helped unite the chapter in a common goal. “Many of us felt we needed to distance ourselves from the project,” he said, “as it could seriously hurt the international reputation of our gaming industry.”

Fasce, who was then the Italian IGDA president, wrote an open letter published on March 19th, 2011, signed by all other members: “While we agree that making students part of a project like this is commendable,” it said, “we would like clarifications on why the project was advertised as being on the same level of quality as other games.”

Unfortunately, the release of the letter would be the beginning of a whole new set of problems for Fasce.

“I started receiving phone calls on my personal cell phone from both Carbone and Marco Accordi Rickaards, who had long been his partner and associate, [and who] used to post together on the Playfields forum,” Fasce said.

While, initially, the phone calls were diplomatic enough—asking Fasce to simply revise the IGDA’s letter—soon their tone turned ominous and threatening. “They were quite clear that I wasn’t doing myself any favors in making them my enemies. I definitely had some sleepless nights in that period,” he said. Under pressure, Fasce decided to step down as president of the IGDA. “This caused a lot of drama in the chapter again,” he said, “with people telling me I was a coward for giving up the fight.”

In the end, Fasce decided to leave Italy for good and, years later, notes how the people that were most vocal about keeping their distance and calling him a coward were, ironically, the first to work with those behind the Gioventù Ribelle project.

“Now I work in the UK, I barely follow what is going on in the Italian industry,” he said. “But it seems to me that, if we have to find someone who was hurt by this project, it would be the students who were involved in it. It most definitely did not stop the careers of those managing the project. 12 years later, it almost seems the opposite, frankly.”

The return of Ribelle

After being taken down just over a week after launch, the official website promised that Gioventù Ribelle would be back and better than ever. No dates were given, nor was a timeline presented, so naturally Italian game developers and journalists were skeptical.

But Gioventù Ribelle did come back as a functional FPS, sort of. The “new” Gioventù Ribelle was still just a single-level demo (instead of the three levels promised), but it was historically accurate, visually promising, and free of bugs. It was a distinct improvement.

The only thing is, this “new” version was a different game entirely, one developed by a dev team managed by Daniele Azara, another member of the Playfields forum. Called XX – La Breccia, the more impressive one-level demo became the unofficial second version of Gioventù Ribelle. Though the FAQ for XX – La Breccia states that the game is not related to Gioventù Ribelle but is an independent product that took five months to make, there is ample evidence that the two were connected, at least during the period between La Breccia’s September 2011 launch and March 2012, when a video of a “Gioventù Ribelle XX La Breccia beta” was uploaded to YouTube by Italian video game account Parliamo di Videogiochi.

La Breccia received positive comments from players and fans of the Risorgimento historical period, though some thought it was just a way to cover up the disastrous release of the original, government-affiliated game—especially when it was suggested that Azara used to work with Carbone. The comments section of an Ars Ludica article published by Tagliaferri is filled with speculation about the connection between the two games and its mysterious dev team. “It seems Daniele Azara is involved,” reads one comment translated from Italian to English. “A person who has been hands and feet inside AIOMI and collaborator with the unnamed. Always bad people.”

Azara himself seems to have responded to these comments on October 6, 2011, as a username reading Daniele Azara that features his current Twitter profile picture wrote: “I wonder: why don’t you download the XX – La Breccia beta instead and tell us what you think? The whole team and I will be happy to use the support and feedback you want to give us. It would be great to talk about the little product we made, instead of having to explain why misinformation is so demeaning and frustrating.” (Azara declined to comment for this story.)

That same user also wrote “Yes in 2003 I founded Blacksheep together with five partners, one of which was Raoul Carbone. I then exited the aforementioned about eight months later due to design and business incompatibilities. While I don’t see how this is demanding to my career, I hope I answered your curiosity.”

The conversations and suspicions surrounding the project, however, didn’t last long, as La Breccia’s Gioventù Ribelle branding was removed in April 2012, once again erasing the original game’s legacy from the internet.

The ghost of Gioventù

Today the Italian gaming industry is doing much better than it was a decade ago. It boasts medium-sized studios like Ubisoft Milan which are responsible for international successes like the Mario + Rabbids franchise, and several indie studios like Santa Ragione (Saturnalia) and LKA Interactive (Martha is Dead). But all of this, we can safely say, is no thanks to the fiasco that was the Gioventù Ribelle project. While it was an attempt to celebrate the “heroism and patriotism of brave young people,” it had quite the opposite effect.

Ironically, for all of Prime Minister Meloni’s talk about the brave youth of Italy, she has done very little for them, aside from campaigning to revoke basic income by attacking teenagers for “doing nothing but playing video games all day” and backing a video game that ended up being an unmitigated disaster.

In a bizarre juxtaposition, the youth of the Risorgimento and the students who worked on Gioventù Ribelle were both inexperienced young people sent to the frontlines, in the futile hope of creating something better for their future. Questions about Gioventù Ribelle linger over a decade after its disastrous launch: did the Italian government really approve the use of students to develop a game that was supposed to put Italy on the map? Who were the other “supervisors” behind it, and did they enjoy the benefits of the purported half a million Euros in marketing money? Why is it so hard to get anyone to talk about it and why do so few seem to be interested in discovering the truth?

While researching this story I reached out to Carbone and his collaborators, Italian devs and journalists working in the industry at that time, and even Meloni’s representative. Most did not respond to multiple requests for comment, and many who did were hesitant to give explicit details in fear of retribution from the supervisors of Gioventù Ribelle and, perhaps, the government.

I even received messages from certain respondents that were not unlike those Fasce got back in 2011. “If I were you, I would not keep researching this topic,” warned one, who did not wish to give their name. “The people who managed the project still work in the industry, it would be quite embarrassing if you kept researching this topic,” said another.

More than a decade later, it’s clear that Italy, its politicians, and many of its game developers wanted to eradicate all traces of Gioventù Ribelle and its rebellious youth in an attempt to cover up the many inadequacies that led to its creation. The forums and websites connected to the game have long been dormant or removed from the internet, accessible only via archives. Today, Carbone is president of VIGAMUS, the video game museum of Rome. Meloni is the prime minister of Italy. Azara is the head of Italian indie studio One-O-One Games. Fasce no longer lives in Italy and works on games out of London. Gioventù Ribelle is mostly gone, trapped in the dark corners of the internet, where only the truly determined can find remnants of it.

Update 03/01/2022 1:55 p.m. ET: We’ve edited this article to reflect a source declined to comment.

More Stories

What Pc can operate Fortnite at 144 FPS?

8 new FPS online games you will need to play for no cost in the course of Steam Subsequent Fest

The Very best Indie FPS Video games